In the ever-more analytical world of professional sports, how should we measure the success of a team owner? Since financial profit is virtually guaranteed thanks to leagues’ monopoly power, any meaningful metric must look beyond the bottom line. Should we base our evaluations on wins and losses? Or should we consider team owners’ roles as leaders and community partners?

For John Henry, the principal owner of the Boston Red Sox, the current baseball season will go a long way toward determining his legacy on the diamond and beyond.

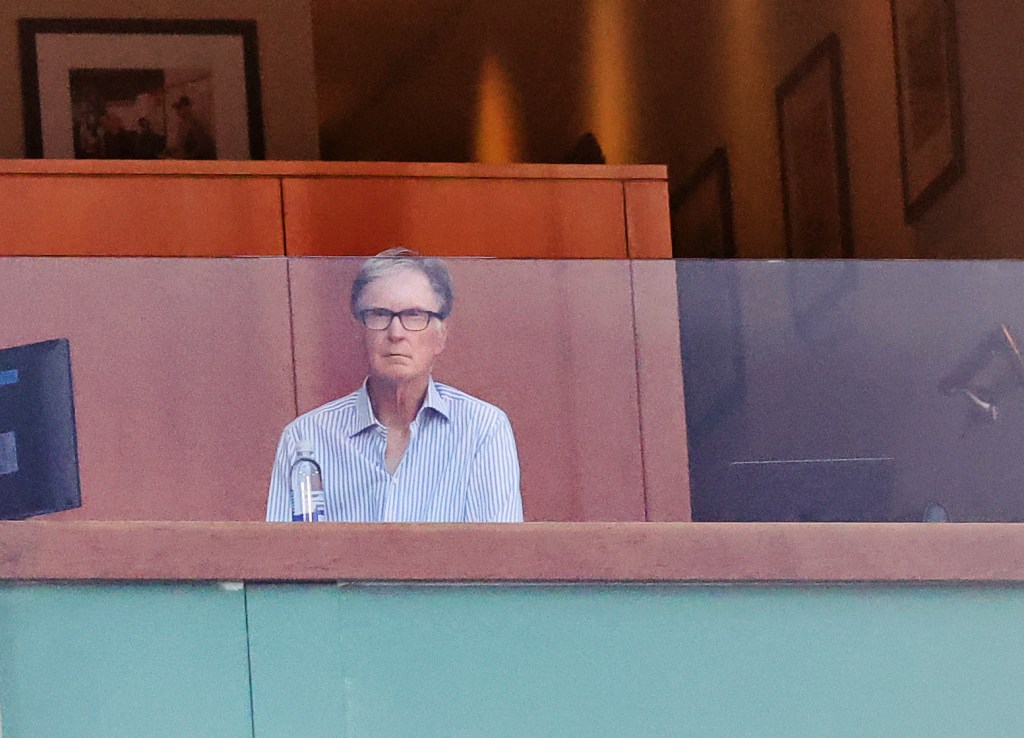

Henry, whose tenure in the Fenway Park ownership box includes the team’s four World Series titles (2004, 2007, 2013, and 2018), has in recent years seemed to eschew the local spotlight. After several years of poor on-field performance and questionable personnel decisions, by the end of the 2024 season Henry had earned a reputation among some die-hard fans as uninvested and aloof – more concerned with business dealings elsewhere than with his floundering Red Sox.

In February, that story seemed to change. Just days before the start of spring training, Henry approved a major new expenditure: a whopping $40 million-per-year contract for free agent star Alex Bregman. With eye-popping numbers at Fenway and two World Series rings, Bregman’s arrival helped quiet criticism of ownership’s reluctance to spend. In the hours after the deal became public, a photograph went viral on social media: an image of John Henry seated before a fireplace in a luxurious living room, smoking a thick cigar.

Originally posted to Instagram by Henry’s spouse and fellow executive Linda Pizzuti Henry, the photograph seemed designed to anchor a new narrative of team ownership’s boldness and engagement. Peaking behind the curtains of power, fans saw a man at the top who seemed, finally, to care.

As Sox fans well know, the Bregman deal continues to have profound consequences. The All-Star third baseman appears poised to lead the Sox down the stretch. Meanwhile, his predecessor at the hot corner, Rafael Devers, is now a member of the San Francisco Giants. Ownership’s power to shape the identity of Red Sox personnel remains at center stage on Jersey Street.

While the most famous and highest-paid, the players on the field are just a small subset of the workforce that brings Fenway Park to life 81 times every summer. Last weekend, during the team’s sold-out series against the Los Angeles Dodgers, the park’s service workers walked out on strike. Their union, UNITE-HERE Local 26, has been in stalled contract talks for months with Aramark, the company that runs Fenway’s concession stands.

The workers, many of whom have punched the clock at Fenway for decades, receive wages that fall well below those of their counterparts elsewhere in Boston and in other MLB ballparks. This season Fenway’s servers and bartenders have also faced new challenges, in the form of hi-tech automated check-out machines that seem designed to degrade and devalue their jobs. As in many other workplaces around the country, from film studios to assembly lines, the staff at Fenway are seeking contractual guardrails that will allow them a seat at the table to shape the future of service automation in the park. In the wake of the three-day strike, Local 26 announced that they remain ready for further talks with Aramark, and that further job actions are on the table if a fair contract is not forthcoming.

Throughout their campaign, the members of Local 26 have urged John Henry to take an active role in brokering an agreement. Like other bosses who choose to subcontract parts of their operations to other companies, Henry and his fellow owners can claim to not be involved in labor disputes and attempt to remain above the fray. So far, this appears to be Sox management’s approach, a state of affairs that begs a question: what happened to the hero with the cigar? Wouldn’t a great team owner have the courage and vision to use their own considerable negotiating power – including the possibility of revisiting future subcontracting agreements – to ensure that everyone who works at Fenway Park is treated fairly and has the opportunity to thrive?

As Red Sox fans – myself included – know all too well, most players don’t stay in Boston more than a few years. Bregman himself can opt-out of his contract after this season. The members of Local 26, on the other hand, are in it for the long haul. Moreover, the contract that they ultimately sign with Aramark will shape the quality of employment at Fenway for the foreseeable future. Why wouldn’t John Henry do everything in his power to make sure these essential Red Sox team members get a fair shake?

Daniel A. Gilbert is Associate Professor of Labor & Employment Relations and History at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. He is the author of “Expanding the Strike Zone: Baseball in the Age of Free Agency”

Originally Published: